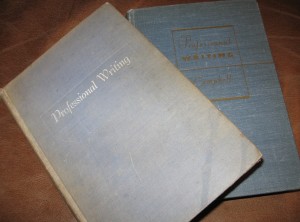

A few months ago, I was in a small antiques shop in Oklahoma City when I came across a faded, worn hardcover lying on a cluttered table. There was no dust jacket, no cover art whatsoever. The buckram had originally been blue; now it’s faded to a steely gray, and the spine is a brittle, sun-faded brown.

Because of my allergies, I forced myself years ago to give up used books. No collecting. No browsing through the musty aisle of tempting treasures. No rare or old editions. I live in the desert of no old books.

But now and then I pick up a volume to give it a look … as an individual crawling in the sand clutches a cup of water.

This ugly book had nothing attractive about it. However, centered on the cover were two words in white script: Professional Writing.

My breath caught. I pounced.

It was indeed a text on writing from Walter S. Campbell, founder of the professional writing program at the University of Oklahoma. A man whom I consider to be my literary great-grandfather. Campbell wrote numerous books on old west history and biography under the pen name Stanley Vestal. He taught fiction writing in OU’s English department during the 1930s and ’40s. This was the heyday of the American short story market. Campbell’s students were so successful at selling their work that trouble began brewing with other English faculty whose students were not selling. Whether the problem was sour grapes or simple jealousy, the rift grew so serious that in the 1950s, Campbell and his students walked out.

Where were they going to go?

The journalism school on campus was just getting started. Its director needed students, even if they weren’t interested in working on the fledgling newspaper. The school changed its name to Journalism and Mass Communication, and Campbell and his class settled in. It became an odd alliance that has somehow worked down through the years, with PW still focused on teaching the craft and methodologies of writing that have worked since Aristotle. Students are still selling their work, provided they work hard and get their manuscripts in the hands of editors. Students have included various novelists such as Tony Hillerman, Louis L’Amour, Carolyn Hart, Curtiss Ann Matlock, and Jim Butcher, to name only a few.

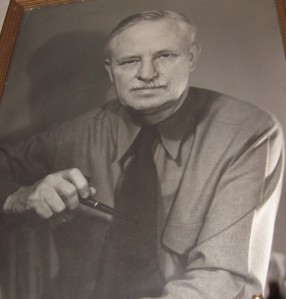

When I was a student in the program, I took “Writing the Short Story” in a classroom dedicated to honoring Campbell. It had a brass plate on the door, designating it as the “Stanley Vestal Memorial Classroom.” Inside, students sat at long, blond-wood tables. Large glass display cases at the back of the room held copies of Cambell’s books. His portrait hung on the wall, and it was painted in such a way that his eyes followed you around the room. Until I took the class, I’d never heard of my major program’s founder. But I learned about him and what he stood for and believed in when it came to writing.

He was followed in the program by a fiesty writer named Foster-Harris. Google the name. You’ll find his books on plotting still available. Foster is my literary great-uncle. His breakdown of story climax is one of the best I’ve encountered. Then came a teacher called Dwight Swain. Dwight is my literary grandfather. He’d retired from the classroom by the time I enrolled, but I was assigned his text on writing, TECHNIQUES OF THE SELLING WRITER, and I read it until the binding split. If you met Dwight at a party, he’d always ask what you were working on, and if you confessed you were stuck, he could put his finger on the problem instantly.

One of his ablest pupils was a hard-headed Yankee named Jack Bickham. It took Dwight many patient coaching sessions before he finally hammered the principles of story craft into Jack’s stubborn head, but once Jack “got it,” his career took off like a rocket.

Jack shone best, however, in the classroom. His personality might be intimidating, but his teaching was phenomenal. His ability to explain the writing craft opened doors to me and explained mysteries that had kept me stymied as I attempted to write my first wobbly stories. Jack was my literary father.

But today’s blog is supposed to be more about Campbell than his successors. In the antiques shop, I picked up the battered old book and opened it. After hearing so much about his teaching, this was the first time I’d actually gotten my hands on his textbook.

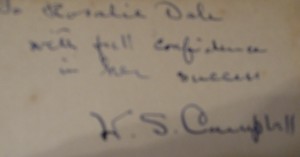

It was dated 1937, and he’d autographed it to a student named Rosalie. Not only do I now have his book, mine to study and learn from, but I have his signature. In my imagination, I can conjure up a tall, distinguished man–a pipe in his teeth–scratching out a rapid little note with his fountain pen. How proud and excited Rosalie must have felt, standing there–perhaps after class–while her teacher signed her copy.

Last year, I went to a local estate sale and was digging around the bits and pieces remaining in the last hour of the sale when I turned and saw a large, framed, black-and-white photograph. I recognized him immediately–that wide brow, the strong jaw and tidily clipped mustache, a kind mouth, and the intelligent, deep-set eyes that look right at you. The photo was obviously what Campbell’s oil portrait had been painted from. I had seen that calm, wise countenance almost daily for years–first as a student and later when I began to teach in the program. I bought the photo for six dollars and carried it home with a thrill that hasn’t faded. Today, Campbell’s likeness hangs in my office, directly behind where I sit when I write my novels, where I’m writing this blog now.

It seems to remind me that good craftsmanship is always worth striving for, no matter how tired and discouraged I might sometimes become. It speaks to me of where I’ve come from, of the traditions that have shaped me, and of the training I’ve worked so hard to assimilate.

Yesterday, I found myself in that same small antiques shop I mentioned earlier. On the same table, I came across another battered hardcover book. Its blue buckram cover is a little fancier. There’s still no cover art, but the plain title has been outlined in gold. The cloth has been worn smooth from use and handling. The edges are worn white. There’s no author signature on the inside cover this time. The edition is 1946, almost ten years apart from my other copy. The pages are heavily underlined in pencil by its first, enthusiastic owner.

I see no other changes, no real differences from the 1937 edition. Why buy two copies of a musty old book, written by a man long gone?

Call me a fan. Call me grateful for his legacy.